- Ellis' Newsletter

- Posts

- Your Questions, Answered!

Your Questions, Answered!

Plus: My cartoon In this week's New Yorker

First of all, I would just like to say “phew.” Last week I put a call out for questions, any kind of question, from mundane to deeply personal and I was worried that I wouldn’t get any. But I did! You wonderful people, you. You asked a bunch of questions and this morning I didn’t have to say to myself “What the hell am I going to write about for the newsletter? Why have I chosen to write something every week? Who would do that to themself? What am I even doing with my life? I should have gone to law school.”

Just kidding! I would have failed miserably in law school. I’m very bad at key things like “arguing,” and “remembering things,” and “paying attention,” and “thinking too hard.” I always forget if “overruled” means the objection is allowed or not. The sound of a gavel hammering down on wood scares me and I would have to fight against my instinct to hide under the table. I feel weird when I wear a suit.

Also I’m no good at math or science, not that I would necessarily need those skills for law school, but I figured I would share that since on I’m on the topic. I might as well! Most of the questions you asked were about me and my journey through the world of cartooning.

A lot of you asked about breaking in to the industry. That’s a longer topic, so next week I’ll give a little crash course on that. Today, I’ll be answering other things. Let’s begin!

I got a bunch of questions about tools and process. A few people asked this, so I’m not going to attribute it to one person. Here’s how I work:

Idea generation starts with a button in my head. If the button is switched off, then I’m just going about my day and I probably won’t come up with any ideas. If it’s switched on, then my brain keeps asking “is this a cartoon?” With that running through my head, I can now go about my day and I still probably won’t come up with any ideas, but there’s a better chance that I will.

If the button is on, then everything I do and see becomes PCF (potential cartoon fodder). You begin to notice all the little phrases people hear and take for granted. My favorite example of this is when I heard my dad ask my mom “Is the dishwasher clean or dirty?” At that moment the button was on, and that boring question suddenly got a lot mor interesting. Here’s the cartoon I made from it:

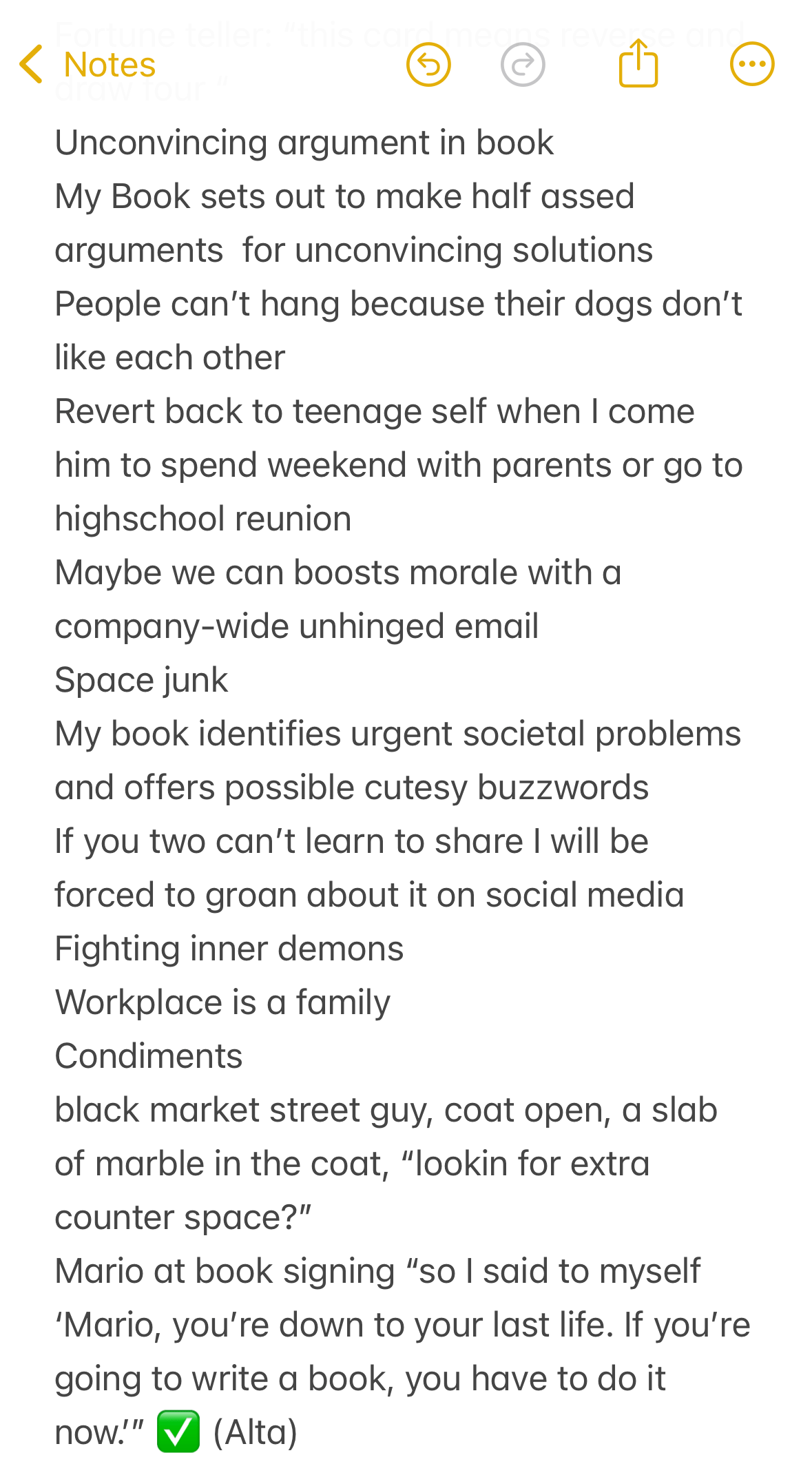

I didn’t go from hearing that to drawing the cartoon. There are steps in between. If an idea, or a phrase, or more often, a topic enters my head, it goes into my notes app. In this example I would have simply written the phrase “Is the dishwasher clean or dirty?” Here’s a screenshot of my notes app:

Most of my topics die here. But sometimes they go on to the next phase, the sketchbook, and if I figure it out from there, they get drawn and submitted. If they sell, I put a little green check mark next to it in the notes app for no reason other than it makes me feel good.

From notes app to final

Figuring out the cartoon in the sketchbook may be easy or hard. After I sketch it out, I put it through a rigorous process to determine if it’s worth drawing (texting all my peers and asking if they think its funny.) If it’s good, I draw it.

I draw digitally. I have since 2015. I haven’t drawn a finish on paper for a New Yorker cartoon ever. These days I draw on an iPad with an iPencil, and iReplace the tip every couple of months. I draw on a program called Clip Studio. I love this program. Most of my peers use Photoshop or Procreate, but I will always recommend Clip Studio Paint. If anyone who works for Clipstudio sees this and wants to give me a free upgrade to the more expensive fancy version, I won’t stop you. I buy packages of digital pens and play around and figure out my favorites from there.

Ok, enough about my process. Next question!

Writer Ollie Masters asked me about my influences. In no particular order:

Groo The Wanderer by Sergio Aragonés and Mark Evanier. This was my first comic book and remains my favorite. Sergio made me want to draw but I think Mark shaped my sense of humor. I practiced reading on this comic. At first I would look at the pictures, then I would just read the word bubbles with one word in them. I would eventually work my way up from a few words to reading the whole comic.

Gary Larson’s The Far Side. No suprise there. Like so many, I lived for the Far Side tear-off calendars and stayed up the first night I got one going through the whole thing thus rendering the calendar moot. Had book collections too, of course.

My Peers. Too many to name, but chances are you follow them too. I love browsing their works at cartoonstock.com, a very useful way to get inspired.

Nicole Ruth Starrett asked me what my favorite movies are. Here’s a bunch I love:

John Carpenter’s The Thing

Frank Oz’s Little Shop of Horrors

Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall

Kōji Shiraishi’s Occult (his other found footage movies too)

Every Mission: Impossible movie (even the bad ones)

Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest

Finally, Edith Zimmerman, a fellow cartoonist, wrote me a long question that boiled down to “Is it poor form to post rejected New Yorker cartoons on social media?” It was a long question but essentially she was worried that by sharing them she was violating some cartooning etiquette, or insinuating that The New Yorker was somehow crazy for rejecting them.

I love this question because it contains so much of the anxiety that cartoonists have, particularly new ones, about our relationship with the esteemed publisher. The short answer to this question is “No, it is not poor form.”

When you are first starting out submitting to The New Yorker, even after your first few sales, it feels as if the magazine is bestowing a great honor upon you. It still does, but eventually you begin to see that it’s a two-way street. The New Yorker is not the The New Yorker without cartoons. They need us. When you start to understand this, you begin to see yourself as an artist with more independence. You are no longer “someone who aspires to be a New Yorker cartoonist,” you are “a cartoonist who sometimes sells to The New Yorker.” Cartooning is your job. You sell wares. Magazines may choose to buy your wares. If they don’t, you have other options. One of those options is to share them on your social media, building your name and sharing your work. When you look at it like that, you are not “sharing rejected New Yorker cartoons” you are simply “sharing your cartoons.”

Remember cartoonists: You are more than a New Yorker cartoonist, and your cartoons, even the ones you sell to them, are more than just a New Yorker cartoon. They are a form of personal expression that could come from no one but you.

Okay! That’s it for today. Thank you all so much for your questions! It really does mean a lot to me. Next week I’ll get into all your questions about starting out in cartooning. Feel free to keep sending me questions if you got em!

What Else?

A little correction for last week’s article about color. The quote “What’s so funny about red?” did not actually originate with Sam Gross, but with Harold Ross, the first editor of The New Yorker.

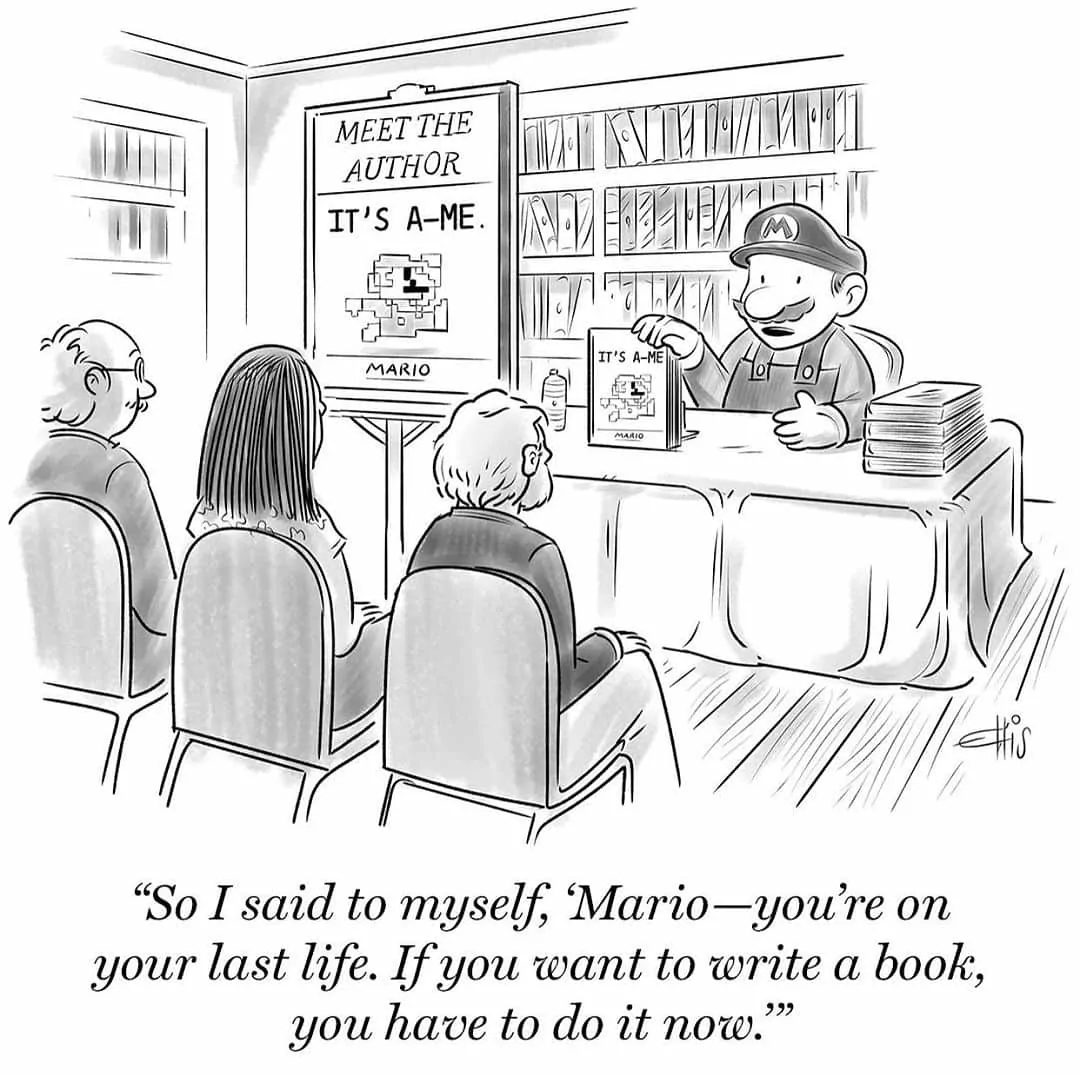

I have a cartoon in this weeks issue! Here it is:

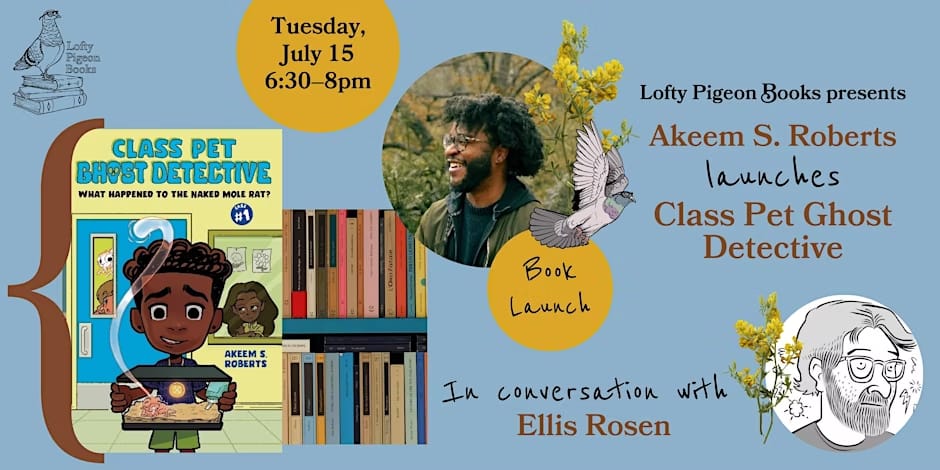

Finally, I am talking with Akeem Roberts on the 15th about his upcoming graphic novel, Class Pet Ghost Detective. Get tickets to come see us talk! It’s going to be fun.

Okay that’s it! See you next week!

Reply